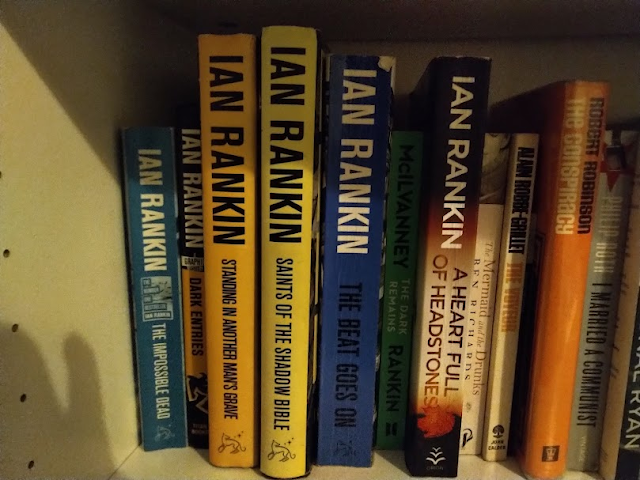

I love Ian Rankin's novels, especially the non-Rebus ones....

2024

is shaping up to be a pretty fine year, in terms of new books by my favourite

writers. In chronological order of their projected release dates, I’m looking

forward to Sixteen Again, Paul Hanley’s soon published tribute to

The Buzzcocks and all they meant to him, before some real fiction

heavyweights have their say. Irvine Welsh, Resolution (12th

July), David Peace UKDK (1st August), Roddy Doyle

The Woman Behind the Door (12th September), Michael

Houellebecq Annihilation (19th September) and Ian

Rankin Midnight & Blue (10th October).

In

preparation for the final book on that list, I’ve set myself the task of reading

the complete works of Fife’s finest purveyor of Caledonian Noir. This is

no small undertaking, as Rankin has been publishing novels for nearly 40

years; not just the Inspector Rebus series, of which there are 25 volumes, plus

a high volume of short stories, two stage plays and an autobiographical

commentary on Rebus’s relationship with Scotland as a whole, but his non-Rebus

oeuvre. Before embarking on this task, I knew that Rankin wrote novels

utterly unconnected to Police Scotland’s most famous intuitive curmudgeon,

because the first thing of his that I read was Doors Open, a rattlingly

good art heist thriller, set in Edinburgh, though it was only this year that I

realised I would have to make my way through the grand total of 11 novels,

including one collaboration, a dozen short stories, a graphic novel and a stage

play. Though I’ve still got a dozen Rebus novels to finish before I’m ready for

the publication of Midnight & Blue, I’ve now finished the rest of

Rankin’s work, which I’d like to discuss below.

The

Flood

(1986): Set in a fictionalised version of Rankin’s home village of

Cardenden, a former coal mining settlement in the less salubrious part of Fife,

his debut novel is perhaps the most consciously literary text of his entire

published output. Starting in the early 1960s, it charts the miserable life of

the outcast Mary Miller. As a child, she fell into a stream of pollution from

the pit that flowed through the village, which turned her hair permanently

white. Initially she was treated with sympathy by the local community, but all

that changed when the young man who pushed her in, died in a workplace accident.

In the present day, still shunned, Mary is a single mother caught up in a

faltering affair with her son’s English teacher. Meanwhile, her son, Sandy, has

fallen in love with a strange homeless girl, and, as both doomed relationships

hit the rocks, mother and son are forced to come to terms with a terrible

secret from Mary's past: Sandy is the product of his late grandfather’s rape of

his mother. Nothing good can come of this situation, set amidst the unforgiving

dark, suffocating, Calvinist village mentality. The book is both gripping and

depressing. It is also considerably better than most of Rankin’s

non-Rebus quasi juvenilia.

Watchman

(1988): A

preposterous espionage thriller, in the manner of Len Deighton, Watchman

tells the story of Miles Flint, a surveillance officer who works for MI5. After

two high-profile operations involving Flint go badly wrong, with deadly

consequences, he is sent to Belfast to witness the arrest of some of the Boys.

However, after accompanying a bunch of rather loathsome Loyalists (are there

any other kind?), he discovers that what has actually been planned is the murder

of the Ra men and then realises that his own life is at risk. As the executions

are about to be carried out, Flint escapes with the aid of one of the Provos, who

is supposedly a former UVF member who swapped sides after reading about the

fellas on the blanket (aye right…). The two of them go on the run, while piecing

together the bones of a conspiracy which goes right to the very core of the

British Government. Fairly predictably, spilling the beans on this, allows them

all to live happily ever after. Flint even manages to patch up his marriage,

which had previously been badly on the skids.

Westwind (1990): The Zephyr computer system monitors the

progress of the United Kingdom's only spy satellite. When this system briefly

goes offline, Martin Hepton becomes suspicious following the death of a work

colleague who suspected

something strange is going on at the satellite facility where they both work, and

then goes missing before winding up dead. Needless to say, Hepton doesn’t

believe the official line of suicide. Refusing to stop asking questions, he

leaves his old life behind, aware that someone is shadowing his every move. The only hope he has of getting to the bottom

of this mystery is enlisting the services of his ex-girlfriend Jill Watson, a

crusading journalist who believes his story. Rather a lot of cross and

double-cross occurs on both sides of the Atlantic as Hepton, Watson and her new

squeeze, the only astronaut to survive a suspicious space shuttle crash, outwit

malfeasant security services and manage to live happily ever after. It’s daft,

but very entertaining and hints at the three novels to follow.

Witch

Hunt

(1993): In the early 90s, recently relocated to rural France and finding that

the Rebus books were niche fiction, rather than blockbuster airport reads, Rankin

made the decision, presumably for financial rather than aesthetic reasons,

to publish some mainstream thrillers under the nom de plume of Jack Harvey,

combining his first-born son’s name and his wife’s maiden name. Stylistically, Witch

Hunt, Bleeding Hearts and Blood Hunt are all cut from the same cloth;

breathless action, one-dimensional or idee fixe characters, labyrinthine

plot twists and unconvincing denouements but, as far as page-turners go, they

aren’t a bad, undemanding read.

In

Witch Hunt, the action begins with the sinking of a fishing boat in the

English Channel in the middle of the night, and the evidence points to murder.

Ex-MI5 operative Dominic Elder comes out of retirement to help investigate, as

it appears that his long-time obsession, a female assassin known as Witch, may

be responsible. Using the boat to get to England from France, Witch left a

subtle trail of clues to announce her arrival and to warn off Elder, who knows

her to be a resourceful enemy, always seeming to be a step ahead of the

authorities. With an imminent summit of world leaders to be held in London,

Witch's probable target seems obvious. A team of detectives and MI5 agents, and

the terrorist, play cat-and-mouse with each other in Scotland, England, France,

and even briefly visit a former associate of Witch in prison in Germany, before

taking the enemy down, with only one high ranking casualty; the nefarious Home

Secretary who turns out to be Witch’s long-estranged father.

Bleeding

Hearts

(1994): This is the only Rankin novel I know of that is written, only

partly I’ll acknowledge, in the first person, though the rest of the narrative

is told in the third person, which creates a slightly uncomfortable, if not

clumsy, atmosphere. It is also the only novel I’m aware of that is told from

the perspective of a haemophiliac hired assassin, one Michael Weston. Yes,

we’re talking that level of reality as the wealthy father of a girl he killed

by mistake years ago has sworn vengeance on the killer, hiring an American private detective, the deliciously crass Hoffer,

to track Weston down. Hoffer does, but doesn’t pull the trigger, as the love of

a good woman intervenes and Weston retires from the game, allowing him and

Hoffer to part on equal terms with no blood spilled, of the clotted or

unclotted variety.

Rankin

has claimed that he wrote this book under the influence of Martin Amis's novel Money and that Weston was

influenced by that novel's protagonist John Self, but I can’t see any

connection myself.

Blood

Hunt (1995):

In this final Jack Harvey novel, Rankin recycles the character of

Gordon Reeve, who was Rebus’s nemesis in the first novel in that series, Knots

& Crosses, though he does imagine a different life for Rebus’s former

SAS buddy.

The

novel begins when Reeve takes a phone call informing him that his brother Jim

has been found dead in San Diego. While in the USA to identify the body, Gordon

realises that his brother was murdered, and that the police are more than

reluctant to follow any leads. Retracing Jim's final hours, he connects Jim's

death with his work as a journalist, investigating a multinational chemical

corporation. Gordon soon discovers that he is being watched, so he decides to

ask Jim's friends back in Europe for further information.

In

London, he finds more hints, but no evidence for his brother's sources. After

returning to his wife and son, he finds that his home has been bugged by

professionals. Sending his wife and son to a relative, he determines to take on

his enemy on his own. There are two parties after him: The multinational

corporation, represented by Jay, a renegade SAS member, and an international

investigation corporation, somehow connected with the case.

Travelling

to France, in order to find out more from a journalist colleague of Jim's, they

are attacked by a group of professional killers, resulting in multiple deaths,

and leading to Gordon becoming a police target. Gordon decides to return to the

USA, where he infiltrates the investigation corporation, and learns more about

the history of the case. Then he travels to San Diego, to collect more

evidence, and eventually returns to England, deliberately leaving a trail for

Jay. Their long enmity leads Jay to follow Gordon to Scotland, where Gordon

kills him and his team in a final showdown. Gordon manages to locate Jim's

hidden journalistic material, thus enabling him to hopefully clear Jim's and

his own name. It is by far the best of the three Jack Harvey novels and

offers a glimpse into what kind of a writer Rankin would have become, if

he’d decided to go down the espionage rather than the psychological police

procedural route. Ironically, it was the success of his Rebus novels, not to

mention their increasing complexity and the attendant length of time it took

him to write the things, that caused Rankin to park the Jack Harvey

project.

Beggars

Banquet

(2002): I read the entire collected Rebus short stories in The Beat Goes On,

so when I got this one, I only read the non-Rebus ones and I like them

tremendously. Well worth seeking out.

Doors

Open

(2008): As I mentioned earlier, this was the first Ian Rankin book I

read and, only knowing his work from the Ken Stott Rebus dramas at that

point, it certainly wasn’t what I expected. Mike Mackenzie is a software

entrepreneur who has sold his company for a substantial amount of money but is

now bored and looking for a new thrill. His new-found wealth has funded a

genuine interest in art so when his friend Professor Robert Gissing presents

him with a plan for the perfect crime, he is intrigued. With a vast collection

but limited wall space, the National Gallery has many more valuable works of

art in storage than it could ever display. The plan is to stage a heist at the

Granton storage depot on "Doors Open Day" during which a selected group

of paintings will be stolen. The gang will then give the appearance of having

panicked and fled without the works of art but will have switched the real

paintings with high quality forgeries good enough to convince anyone

investigating the matter that no theft has been committed.

Intrigued,

Mike willingly helps set that plan in motion. As they begin to plan it out, it

becomes clear that they need some "professional assistance" and a

chance encounter with Chib Calloway, a local gangster who Mike went to school

with, fulfils that need, presumably as Big Ger was on holiday at that point.

It’s a good old-fashioned heist yarn, with a surprisingly moral ending. I

suppose if I hadn’t enjoyed it, I wouldn’t have embarked upon this journey

through Rankin’s collected works.

A

Cool Head

(2009): It’s very fashionable to decry Tony Blair, simply on account of

the fact he’s a war criminal who spent his entire Premiership toadying up to

the Great Satan across the pond, but he did do some good things. The Quick

Reads initiative was one of them. Quick Reads were launched by Blair

on World Book Day 2006. By mid-2020, over 100 titles had been published, over

4.8 million copies had been sold and over 5 million copies had been loaned

through libraries.

For

those unfamiliar with the project, Quick Reads are a series of short

books by bestselling authors and celebrities. At no more than 128 pages, they

are designed to encourage adults who do not read often, or find reading

difficult, to discover the joy of books. In a long-forgotten celebration of the

philosophy of lifelong learning, Quick Reads were a collaboration between

leading publishers, supermarkets, bookshops, libraries, government departments,

the National Institute of Adult Continuing Education (NIACE), Arts Council

England, the BBC, World Book Day, National Book Tokens and more. They are used

as a resource for adult literacy teaching and have been used in Skills for

Life and ESOL classes in colleges, community centres, libraries,

prisons and workplaces across the country. They have also been used in

hospitals, stroke recovery units, dyslexia centres, care homes, family learning

groups, pre-schools, organisations working with homeless people and traveller

communities, and Army and RAF bases. In a survey covering 50,000 readers in

2010, 98% said that Quick Reads had made a positive impact on their

lives. Certainly, as someone who taught for many years in Adult Education, I

can vouch for their value in demystifying the vexed concept of reading fiction

for pleasure. In 2018, the programme was due to come to an end because of a

lack of funding. Another thing to thank the Tories for, eh?

What

has this to do with Ian Rankin? Well, in 2009, Quick Reads

published his contribution to the series, A Cool Head. It tells the

story of Gravy, who works in a graveyard. One day his friend turns up in a car

he doesn't recognise. His friend has a bullet in his chest. Gravy is asked to

hide the gun and the body. In the back of the car is blood, and a bag full of

money. Soon Gravy is caught up in a robbery gone wrong and is pursued by some

desperate and mysterious men as well as the police. Thanks to Ian Rankin

for writing this story.

Dark

Entries

(2009): I’ll come clean with you; this is the Ian Rankin book I liked

the least. In fact, I probably dislike it, because of my own prejudices. You

see, it’s a graphic novel or, if you’re an adult, a comic. The story involves DC

Comics character John Constantine, the series Hellblazer, apparently.

The

plot involves John Constantine being convinced to enter a reality television

programme which has suffered several strange hauntings, which is clearly a

thinly veiled satire of Most Haunted and Big Brother. The set

turns out to be not a television programme made for humanity, but for the

denizens of Hell, and John must work out a way to escape from this. I’m not

really sure if he did and, frankly, I’m not bothered. Then again, I doubt I’m

the target demographic for such balderdash.

The

Complaints

(2009): The character of Malcolm Fox, who ends up in at least 4 of the later

Rebus novels, as well as the two dedicated solely to him, is the best and most

satisfying Rankin creation outside of Rebus and Siobhan Clarke, in my opinion.

A dogged, recovering alcoholic loner, with a bad marriage behind him, a drunken

underachieving sister with an attitude problem and an ailing father in a care

home, Fox throws himself into his job with silent gusto. The fact is his job

entails investigating potential misconduct by other officers, hence The

Complaints, makes him a figure to be truly despised by those on the force

as well as off it. The fact he somehow manages to shrug this shroud of enmity

off and solve complex, intractable cases shows us why he ends up back in CID.

In

The Complaints, Fox and his team are tasked with investigating Detective

Sergeant Jamie Breck, suspected of being a member of a child pornography ring.

However, Breck is in turn investigating the death of Vince Faulkner, who was in

an abusive relationship with Fox's sister. This brings Fox into direct contact

with Breck, and as he develops both a friendship and a working relationship

with him, he begins to doubt the validity of his assignment. Despite his

personal connection to the case, and against protocol, Fox gets involved in the

investigation into Faulkner's death. This brings him into conflict with Breck's

superior officer, who harbours a dislike of Fox for investigating a corrupt

officer under his command.

Eventually,

Fox and Breck are both suspended and Fox is also placed under investigation.

However, they continue to investigate Faulkner's death, discovering that he had

links to a bankrupt property developer who appears to have committed suicide.

This leads to further links to members of the criminal underworld, and in turn

to a senior member of the police force, who is found to be responsible for

having Breck framed and for having Fox placed under investigation. When Fox

comes out on top, I actually punched the air in celebration, such is the superb

characterisation Rankin has employed to turn a potentially

mealy-mouthed, paper clip counter into a sleuth supreme. Also, Fox’s activities

take place back in familiar Edinburgh locations which, as Rankin became ever

more certain of his craft, are the best and most fitting place for his fiction.

The

Impossible Dead

(2011): The second and, sadly, seemingly final Malcolm Fox novel is even more

enjoyable than The Complaints, partly because we get to travel to

Rankin’s home turf of the Kingdom of Fife. Proper Fife as well; Kirkcaldy, not

the Vichy Fife of Dunfermline or the lah di dah East Neuk and that

unspeakable posh place east of Leuchars.

Fox

and his team, Tony Kaye and Joe Naysmith, are assigned to an investigation into

Detective Sergeant Paul Carter, who has been found guilty of misconduct. Fox’s

job is to reassure the Fife Constabulary top brass that the

other Kirkcaldy police are clean. Fox visits Paul’s uncle Alan, a seemingly

jovial retired Polisman who had reported Paul in the first place and is drawn

into the murder investigation when Alan is killed, and Paul is framed for it.

Fox and his team must dodge, while exploiting as sources, not only the hostile

Kirkcaldy police but contingents of Fife headquarters CID, Murder Squad, and

even an emissary from London’s Special Branch.

When

Fox visited him, Alan Carter was investigating the suspicious 1985 death of an

Edinburgh lawyer named Francis Vernal, who was involved with Scottish Nationalist paramilitaries in the 1980s. Fox becomes obsessed by

Vernal’s story, in part because there are similarities between Vernal’s death

and Carter’s murder. He interviews various former associates of Vernal,

including his onetime law partner, his widow, a madman, a TV personality, and a

Chief Constable who is herself trying to deal with a group of terrorists.

Eventually Fox identifies the person who killed both Vernal and Carter, but Fox

has to risk his own life to capture them. He does, coming out clean as a whistle,

having wrecked the career of the Chief Constable of Fife in the process. So it

goes, eh?

Dark

Road

(2013): Thus far in his career, Ian Rankin has written three plays: the

Rebus connected A Game Called Malice and Long Shadows, which I’ll

talk about next time, as well as the unsettling Dark Road. Bearing in

mind I’ve not seen any of his plays performed, I can only talk about them in

terms of how they appear on the page. Co-written with Lyceum Edinburgh’s

director Mark Thomson, the play is set in modern-day Edinburgh and

follows Scotland's first (fictional) female Chief Constable Isobel McArthur now

Chief Superintendent of Edinburgh following the creation of Police Scotland, as

she considers retirement and ponders writing a book. As part of that she

reviews the case of Alfred Chalmers a serial killer who killed four girls a

quarter of a century previous, a conviction she has long held doubts about.

What follows is a thriller that throws herself, her daughter and her colleagues

into a psychological battle against Chalmers. As a piece of writing, the ending

may be a tad predictable, but I’d imagine it is a bit of a chiller to sit

through. I’d like to see this live I must admit.

The

Dark Remains

(2021): While I’ve long been an admirer of the football writing of the esteemed

Hugh McIlvanney, I’m sorry to report I was unaware of the works of his

brother William. This is a situation I intend to remedy when time

allows. Following William McIlvanney’s death in 2015, he left among his

papers an unfinished draft of a police procedural, involving his Glasgow copper

Jack Laidlaw. It was the fourth Laidlaw novel but set chronologically before

the other three. Ian Rankin took

on the project and produced the vivid and compelling The Dark Remains.

Jack

Laidlaw has been moved to the Central Division of the Glasgow Crime Squad. He

is a DC working for DI Ernie Milligan. Robert Frederick the commander of the

Glasgow Crime Squad assigns DS Bob Lilley to keep an eye on him, saying

Laidlaw's reputation has always preceded him .... who has he rubbed up

the wrong way this month? .... he’s good at the job, seems to have a sixth

sense for what’s happening on the streets (but) he needs careful handling, if

we’re to get the best out of him.

The

novel is set in October 1972, early in Laidlaw's career. Bobby Carter the

right-hand man and lawyer cum money launderer for Cam Colvin one of Glasgow's

top gangsters has disappeared, and then his body is found, in enemy territory.

John Rhodes is Colvin's main rival; not minor gangsters like Matt Mason and

Malky Chisholm. Milligan pontificates to his team that the graffiti tells him

that the Cumbrie are encroaching on the Carlton turf. A stabbing is one

hell of a calling card, wouldn’t you agree? He assumes, like other

gangsters, that a rival gangster arranged Carter's death, and gang warfare

intensifies. But Laidlaw sees in Carter's home evidence of recent painting to

cover up bloodstains from a domestic dispute after Carter was stabbed by his

bullied wife and children. His wife eventually confesses to Laidlaw, to keep

the children out of it. Laidlaw bypasses Milligan, who he despises, by

reporting directly to Commander Frederick. When the team are celebrating the

end of the case, Frederick says privately to Lilley that if he doesn’t

manage to detonate himself in the near future, he might be in line for a swift

promotion .... (although he is) not exactly a team player. This is a great

book by two great writers about a great fictional cop.

In

a dozen books time, I look forward to discussing 25 great books involving

Scotland’s greatest fictional cop.