The

accurate and subsequently accepted definition of abstract concepts, both new

and existing, has long been an essential part of the mechanics of philosophy,

with theoretical positions forming the basis of future reasoned debate. It’s a

dirty business, but someone has to do it. Take, for instance, the subtle

semantic differences between the words life and existence. How

can we adequately express the varying shades of meaning, whether metonymically

or metaphorically, between the two? Life, other than when it signifies a

long and indefinite period of incarceration, seems to be associated with

positive connotations of enjoyment and experience, whereas more passive associations

of merely surviving, often in straitened circumstances, are linked to existence.

Essentially, perhaps, the two words are under consideration contiguous to the

terms doing and being, as they are understood in the

philosophical domain.

In

the current era, I would suggest that the terms life and existence

may be best illustrated by the Government’s restriction and almost decimation

of personal freedom, by means of what has come to be known as “the lockdown.”

It is not my purpose to consider the medical or ideological validity of such

actions in this piece, though it is essential to mention that the contradictory

statements and actions of the Prime Minister and his associates suggest that if

Britain were to become a Police State, then the most appropriate constabulary

to wield executive power would be the Keystone Kops.

Rather,

I refer to this curtailment of liberty as a way of showing that life is

poetic in its vibrancy, while existence is unending, monochrome and

prosaic.

This

leads me to the question whether it is even possible to exist under lockdown

for as much as another 18 months, denied the opportunity to live as social

beings: unable to visit pubs or restaurants, to watch or play sports (the

inevitable cancellation of the 2020 recreational cricket season hurts me

grievously), or even to associate with family and friends. If the alternative

is to risk a second wave of infection from COVID-19, then it seems that the joy

to be found in life may be worth the risk of death, to avoid the

privations of existence.

When

the only legal exceptions to house arrest are trips to the shop or the Michael

Gove endorsed exercise hour, the task of filling the hours from one day to the

next becomes almost as important as the chosen tasks themselves. Aside from

unnecessarily long sleeps and the excessive consumption of alcohol, those of us

cursed by a restive intellect require more active diversions than the passive

consumption of television or films. Music can act as either a passive or an

active diversion, depending on the level of concentration the listener brings

to the activity, though the most fulfilling activities for me involve the twin

disciplines of reading and writing and this piece will contain writing that is

a reflection on the reading I have been consumed by since the outbreak of this

virus became the sole subject of public debate.

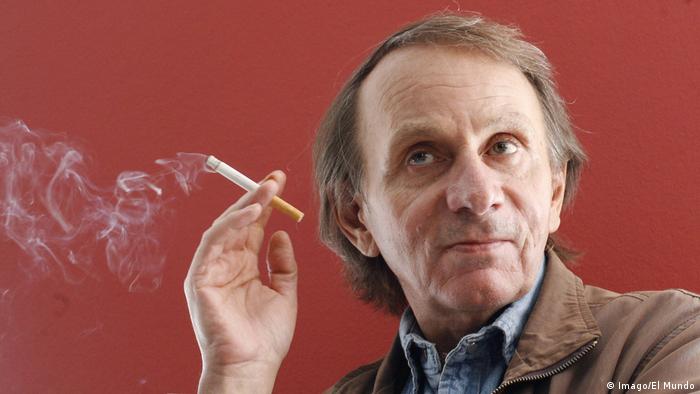

Over

the past two months, I have read, in random order, all eight of the published

novels by the French author, Michel Houellebecq. What was born out of intrigue

has matured into an obsession that has recently seen me begin to investigate

Houellebecq’s more recondite activities as a singer and rapper, as well as the

somewhat recherche non-fiction elements of his craft. It is relevant to note

that the next publication of his work, translated into English, will be his musings

On Schopenhauer, due out on May 15th. With the publication of

the latest books by Roddy Doyle, David Peace and Harry Pearson, all being

delayed for a minimum of six months, Houellebecq’s philosophical considerations

have now assumed greater importance than I could have imagined at the start of

this year.

Why

Houellebecq? Good question. Serendipity would probably be the most honest

answer. An email from Waterstone’s alerted me to the fact I had a

tenner’s credit on an old loyalty card. This scheme was ending, so I needed to

use it or lose it. Around the same time, while farting around on the internet,

researching the Hitchens brothers for a piece that never got written, I came

across references to Houellebecq as being as much of a contrarian as the late

Christopher, though obviously ideologically very different. Intrigued by this,

I took my voucher to Waterstone’s and bought my first Houellebecq, on the basis

it was the only one of his priced at £9.99. Thus, my journey began with La Carte et le Territoire (The Map and The Territory). Subsequently, I ploughed through, in the following order

: Soumission, Sérotonine, Lanzarote, Extension du Domaine

de la Lutte, La Possibilité d'une Ile, Platforme and Les Particules élémentaires.

Despite my use of the original French titles above, I

read the books in English, so my thanks go out to the translators: Gavin Bowd,

Paul Hammond, Lorin Stein, Shaun Whiteside and Frank Wynne. As regards the

books themselves, I will address them in chronological order and refer to them

by their translated titles, other than Houellebecq’s first two novels. The

facile and lazy Whatever does not do justice to the complexity and

importance of his first novel Extension du Domaine de

la Lutte, so I will use the original title, not out of pretension, but

for reasons of accuracy. It also inspired the title of this blog, though

with a sense of regret that Houellebecq isn’t German as I could have named this

piece Sein Kampf. Similarly, I regard Atomised as glib and

excessively informal rendering of Les Particules élémentaires, so I will

use the American title of the novel, The Elementary Particles, instead.

What follows is a series of observations related to the collected works

of Houellebecq, though it is important to provide some context to his work and

the world it sprang from.

In each and every novel, Houellebecq creates a different

but instantly recognizable personal and public dystopia, set either in the

current era or in the future. The persistent feature of the narrative voice in

each novel is the repeated insistence that it is only the reader who views

these portrayals of dysfunctional societies in a negative fashion. Despite persistent

allegations of an Islamophobic world view, which I will seek to refute later,

Houellebecq is intent on representing society as he sees it, as demonstrated by

the quotation from his poem Unreconciled that prefaces this piece. Consequently,

as a self-identified misanthropic cynic, he contends he is presenting the world

as he sees it when he describes the inevitable breakdown of human relations;

work is always unrewarding, except in financial terms, families are toxic, property and material goods are only of

interest as functional objects and, perhaps most crucially, romantic

relationships are doomed, witness the tragic deaths of Michel and Bruno’s life

partners in The

Elementary Particles,

or Valérie in Platform. However, it should be noted that the most

affecting death in all of Houellebecq’s novels, which include his own murder in

The Map and The Territory, is that of the unconditionally loving pet dog

Fox in The Possibility of an Island.

The

only satisfaction in Houellebecq’s world is found in personal sexual

gratification, where the presence of another human being is purely as a

vehicle, if not a receptacle, of the narrator’s requirements. All emotion and

human connection are absent; sex is transactional like all other purchases in

this world. Ironically, the uncommitted and disconnected Houellebecq shows more

than superficial similarities with the emotionless Mersault of part one of L’Etranger.

Yet Houellebecq is, perhaps mischievously, uncritical of such a state of

affairs, repeatedly asserting that because this is how life is, we are

powerless to change things, even if wishing to do so was desirable.

Houellebecq

was born on the island of Réunion in either 1956 or 1958. The product of a

chaotically dysfunctional family, where his parents were largely absent from

his upbringing and subsequently uninterested in his progress as a human being,

he explains the confusion over his birthdate as the product of his deeply

unreliable mother forging a replacement birth certificate to allow him to

attend school two years early, thus absolving her of any responsibility for

looking after him. This demonstrates the beginning of the highly troubled

relationship between the two that reached its apogee in 2008 when his mother

published her account of events in his formative years, while engaging in a

very public spat.

After

school, Houellebecq attended agricultural college rather than university, which

has effectively enabled him to play up to the stereotype of the gauche

outsider, rather than a member of the French intellectual elite who were

educated at one of les grandes écoles and published his first poems in

1985. His first book was an analysis of H. P. Lovecraft, Against the World,

Against Life, but it is with the appearance of his debut novel Extension du Domaine de la Lutte in 1994 that

Houellebecq’s importance as a writer becomes apparent.

In

his late 30s and working as a computer administrator for the National Assembly,

Houellebecq initially appeared as an unlikely spearhead for any new cultural

movement, when fame was thrust upon him after Extension

du Domaine de la Lutte became not just a literary

phenomenon, but a philosophical one, admittedly within the rarefied world of

French scholarship, in terms of the message the book appeared to transmit. A

nameless, bored computer programmer from the faceless Parisian banlieus

is seconded to visit small towns, for the purpose of delivering IT software

courses to local civil servants, who have neither the aptitude nor interest to

take on board what he is telling them. He is accompanied by a work colleague he

despises, who spends his leisure time attempting to lose his virginity aged 28,

while the narrator gets incoherently drunk. Eventually the work colleague kills

himself in a drunken car crash and the narrator, acerbic, misanthropic and

dissociated to the end, returns to his original job just before Christmas,

which he refers to as December 25th.

To attempt to restrict the intellectual parameters of

this work by imposing the title Whatever on it, is a kind of

anti-intellectual vandalism that has not been seen since the era of the

Luddites. Extension du Domaine de la Lutte creates the world in which

Houellebecq continues to inhabit; unsuccessful, defeated middle-aged men living

in squat apartments among swathes of faceless, grey apartment blocks in the

exurbs of a version of Paris utterly at odds with the romance and glamour of

most literary representations. It is existence rather than life. Even

George Orwell invested a sense of hedonism in his depictions of Parisian

poverty in the late 1920s. Houellebecq’s version of Paris can be compared to

Bukowski’s take on 1950s and 1960s Los Angeles; Hollywood and Sunset Strip are

utterly absent from his narrative, which is centred on the interior of a sorting

office, dive bars and low-rent apartments. Houellebecq’s characters are not bon

viveurs or epicures; their diet almost exclusively consists of top of the

range microwav meals from neighbourhood mini supermarkets, while the daily

routine of getting drunk is just what they do after work, when they’re not

jacking off to pornography. Again, this hints at Houellebecq’s other similarities

with Charles Bukowski. In the same way that Bukowski bases his main character,

Henry Chinaski, on an idealised or expanded version of himself, the first

person narrator in six of Houellebecq’s works of fiction can be seen a

representation of the author, to a greater or lesser extent.

Houellebecq’s

second novel, Les

Particules Élémentaires published in the

English-speaking world with the brutal and inadequate title Atomised in

the UK, and the vastly superior The Elementary Particles in

the USA, was a breakthrough, bringing him national and eventually international

fame, as well as provoking controversy for its intricate mix of social commentary and passages of graphic

depictions of sexual acts, written in a consciously anti-erotic style. Written

in the third person, the book narrates the fate of two half-brothers: Michel

Djerzinski, who became a prominent biologist, highly successful as a scientist

but utterly withdrawn and depressed, and Bruno Clément, a French teacher,

deeply disturbed and obsessed by sex.

The

brothers’ lives are not treated consecutively or concurrently, but

elliptically. Bruno retreats to a psychiatric hospital after the death of his

life partner and drops out of the book, while Michel responds to the death of

the woman who loved him for almost 30 years by taking a job in a research

laboratory on the very edge of the Wild Atlantic Way, in Clifden, County

Galway. Here, as we learn in postscript, Djerzinski engineers human DNA in a

way that turns the species into immortal neo-humans. Unlike

many of his later works, in which he has been accused of peddling Islamophobia,

misogyny or racism, the main criticism of Les Particules Élémentaires is that it is a manifesto for eugenics.

Plainly, this is not the case; the novel mainly focuses on metaphoric

representations of the dual sides of human nature, in a kind of Jekyll and Hyde

way. The difference being that neither the sensual hedonism of Bruno nor the

scientific detachment of Michel offers any protection against the inevitable

passage of time and the unbending pressure of society’s requirements.

It

would be more accurate to describe Houellebecq’s next work, Lanzarote,

as a novella, as it only extends to 84 pages. This is not to underestimate its

importance, as the ideas within provide much of the plot and ideas contained in

both Platform and The Possibility of an Island. Houellebecq

touches upon sex tourism, with detailed, dispassionate descriptions of graphic

sexual acts involving a German lesbian couple who, in a telling minor aside,

the narrator fails to contact on returning home, having inaccurately recorded

their telephone number. The other character, a slightly pathetic, lonely and

defeated Belgian, leaves the island without warning after completely failing to

impress the endless series of women he has failed to seduce. The narrator is

surprised to see the Belgian on the television news, revealed as part of

massive child sexual abuse case that involves a sinister quasi-religious cult,

which is loosely based on the Raelians. Lanzarote may be a minor work,

but Houellebecq’s later career points to its relevance.

Certainly, his next novel, Platform, is a ruthless

and excoriating take on tourism in general and sex tourism in particular. It is

unique among Houellebecq’s works in its deliberately comic depictions of a

gauche and socially inadequate set of tourists, including the narrator

describing his holiday attire of a Radiohead t-shirt and long shorts as

being proof of how “pathetic” he is. The fact that the repeated depictions of

sex acts with prostitutes do not provoke reactions of disgust in the reader,

suggesting that the commodification of all personal relationships affects us

all. The real point of contention in this novel are the numerous voices who

have accused Houellebecq of rampant Islamophobia in this novel, and in his

later work, Submission.

The question of the actual existence of Islamophobia is

one that can be answered only with reference to the specific social and

cultural conditions of particular counties. In England, as opposed to Britain,

the continued prevalence of a dominant Oxbridge elite that retains control of

the Law, the Press, Parliament, the Military and most of the top Universities,

has enabled a narrative based on the attitudes that became ingrained after the

Glorious Revolution and were reinforced by the Empire, to retain cultural

control. The Church of England, as an institution, has little if any influence

on the morals and ethics of the ordinary populace, but the many tentacled hydra

of the British Upper Classes, extends its influential power over all aspects of

society. Any belief that is not the Anglican Communion is regarded as, by definition, morally

and intellectually inferior. This mindset continues to stigmatise all other

religions. Non-conformism is the faith of the Valleys and the coalfields.

Catholicism is the amoral refuge of drunken, violent Irishmen. Judaism has not

gained a better press since Shylock’s day. Other non-Christian faiths are the

preserve of savages and slaves. Islam is seen as the modern Catholicism; the preserve

of violent insurgents, dedicated to the destruction of Britain. Islamophobia is

therefore an institutional prejudice, harboured and encouraged by those who maintain

the legal, cultural and financial infrastructure of society. This is not the

case in France.

Despite assumptive British ignorance to the contrary,

France has not effectively been a Catholic country since 1789. The refreshingly

anti-clerical nature of the Revolution was demonstrated by the Declaration

of the Rights of Man and the Citizen that stated “Every citizen may,

accordingly, speak, write, and print with freedom,” though this was followed by

the ominous caveat that each citizen “shall be responsible for such abuses of

this freedom as shall be defined by law.” Following the execution of Louis XVI

in January 1793, the dechristianisation of France gathered pace, as the ideas

of the Enlightenment took hold. Despite the Reign of Terror and the efforts of

Napoleon, the seeds of atheism took hold in France. In 2005, 45% of French

citizens identified as atheists; while this figure had dipped to 29% in 2015, a

further 62% regarded themselves as non-religious. The only reason religion has

not died in France is the arrival of Francophone African citizens, who have

both maintained a residual level of Catholicism and created an exponential

growth in the number of French Muslims.

Significantly,

many of those arriving in France have taken low-paid jobs and moved into the

poor-quality housing of the outer banlieus in Paris and other major

towns, creating ghettoization in the very areas Houellebecq situated his

disaffected and disenfranchised characters earlier in his career. Without a

doubt, Houellebecq has been responsible for provocative and inflammatory

comments on Islam, but unlike the utterings of the barely literate Marine La

Pen or the coarse bigotry of the Far Right in England, his words should be seen

not as sloganeering, but as a part of the general public discourse that

repeatedly shows he is a product of the French culture of anti-clericalism and

semi Socratic outpourings on vaguely formed theories. In short, Houellebecq has often participated

in the typically French philosophical activity of thinking out loud, and in

public, where he is asking himself the hard questions and challenging others to

answer for him.

From

provocative opinions, to provocative artistry, Hoellebecq moved on to the

challenging Possibility of an Island. The book contains three different

narrators (Daniel 1, Daniel 24 and Daniel 25), the latter two being neo-human

clones who live thousands of years in the future, in a post-apocalyptic, arid

landscape, populated by a few thousand “savages,” as well as the anatomically

perfect and hyper-resilient, cloned neo humans. The latter narrators, at the

point of creation, have the full biography of Mark 1, a bitter, cynical and

deeply offensive Jewish stand-up comedian from the turn of the millennium, who was

cloned by an Elohimite acquaintance, to study and internalise. The Elohimites

are based on the Raelian cult, who spend their entire time seeming to worship

alien life who they expect to land on Lanzarote and fleecing gullible

billionaires for all their wealth.

Unfortunately,

the book doesn’t really work for the first half; possibly because Daniel 1 is

so unpleasant. However, once we realise Daniel 1’s narrative is the

biographical account all subsequent Daniels are required to study, the

structure begins to make sense. Daniel 25 leaves his home in what used to be

Barcelona, to walk to Lanzarote, following an event called “the Great

Drying-Up” as the book is by turns poignant and affecting, but never less than

fascinating. It is undoubtedly Houellebecq’s most experimental, though least

successful, work.

In

The Map and The Territory, a photographer becomes fabulously wealthy by taking

pictures of French Ordnance survey maps and expanding the photos to incredible

sizes, producing beautiful and unsettling effects. One of his devotees is the

character of Houellebecq, at that time resident in Ireland, who agrees to write

the text of the catalogue for another show. Unfortunately, Houellebecq is

unexpectedly and brutally murdered. Perhaps the most intriguing innovation is

the use of large sections of Wikipedia, used without comment as descriptions in

the book. The effect is intentionally comedic, as the absolute and utter lack

of opinion in these mundane passages becomes almost surreal with the repetition

of this bland style of reportage. This fits with the consciously distant third

person narrator, to make it Houellebecq’s most obviously stylish novel to date,

but it pales into insignificance when compared to the profoundly cerebral Submission,

which was ironically launched the day of the Charlie Hebdo shootings.

Set

in 2022 amidst a backdrop of an imagined domestic political crisis, whereby the

Front National are deadlocked with the Muslim Brotherhood in a French

presidential election, Submission is undoubtedly the most stylishly

written of all Houellebecq’s novels. A possible explanation for this is that

the narrator, Francois, is a professor of literature at Université de la

Sorbonne Nouvelle. Though while he is eloquent, measured and conservative in

his expression, this is seen as a weakness because he is unable to speak up or

speak out in dangerous, unpredictable times. Indeed, Francois is the first of

Houellebecq’s protagonists to begin his tale in late middle age, rather than

during his putative mid life crisis. Unsurprisingly, Francois views himself as

a failure in his personal and professional lives, no longer able to maintain a

relationship nor produce academic work of merit. However, this is not simply a

story of angst among the aged; it is a subtle exploration of morality and

betrayal.

Unlike

in various interviews, or through the words of his narrators in Lanzarote and

Platform, Houellebecq does not denounce Islam at all in Submission;

instead the transformation of bourgeois, academic, intellectual France, and

especially the capital, into an Islamic Republic under Sharia Law is described

in restrained terms. When the entire professoriate is summarily

dismissed, it is made clear they will be employed again, if they convert to

Islam. The inducement to do so is not a monetary one, but the promise of a

15-year-old Arab girl as a trophy bride. Under French law, while a girl of 15

is still a minor, she is able to give consent to sex. Typically, Francois fails to adhere to any

principles, which makes the reader more judgemental in tone than his previous

actions deserve. Again though,

Houellebecq’s novel springs from the anti-clerical, questioning culture of

French intellectualism, where ruthless ambition is seen as a more serious

character flaw than the sexual abuse of underage girls. Undoubtedly, Submission

is a difficult and at times painful read, but it asks essential questions of

our society. Hence, its impact upon French consciousness is significantly

greater than in other countries who have a differing cultural narrative and

discourse.

In

contrast, Houellebecq’s latest novel, Serotonin, contains some of his

most gratuitously offensive and vacuous writing, specifically uncomfortable

references to his former girlfriend’s pornographic film career, where she

specializes in group sex with dogs. The ludicrously named narrator, Florent-Claude

Labrouste, is a depressed, middle-aged civil servant, who has a pointless job

that involves trying to promote cheese from Normandy in France. Having decided

he has failed in life (we’ve been here before…), he decides to simply

disappear, ending up resident in a holiday cottage owned by a friend of his

from agricultural college days, Aymeric. He is an alcoholic whose farm is on

the verge of bankruptcy. After his family desert him, he attempts to start a

rural insurrection against government policies, but instead shoots himself when

confrontation with the authorities grows near. His senseless death provokes

nothing in Florent-Claude, other than a decision to move back to Paris and live

in a hotel, in obscurity.

The

plot may appear to be both transparent and risible, but Houellebecq’s

experience in constructing such novels of regret and disappointment has honed

his craft. We genuinely pity the narrator’s plight and can almost sympathise at

his insane plan to win back a former girlfriend by killing her son, though

thankfully he decides against such a course of action. Undoubtedly, Houellebecq

is now firmly in the grip of his own late middle age crisis. His twin influences

of pessimism and social conservatism mean his novelistic concerns are

narrowing, but with the trade off that his writing has become forensically

detailed and curiously affecting. Is this enough to compensate for his lack of

a sense of wonder? A younger reader than I would need to answer that.

Of

course, while this may be the end of Houellebecq’s fictional journey so far,

there are other items out there and, armed with the zeal of an obsessive

completist, I ventured through Ebay and Discogs in search of

obscure artefacts. At the time of writing, Houellebecq’s paean to HP Lovecraft,

Against the World, Against Life, has yet to be delivered, though I have

made my way through two other books. Firstly, Public Enemies is the entire

2008 correspondence about ethics, moral, politics and society that Houellebecq

enjoyed with the notable French intellectual Bernard-Henri Levy. Across 300

semi-enlightening pages, they play a kind of ideological ping pong, introducing

more and more preposterous theories and showing off their literary and cultural

knowledge, rather in the manner of small, precocious children throwing a hissy

fit because nobody is paying them any attention. It is, frankly, an inessential

purchase. The same cannot be said of Unreconciled, a selection of Houellebecq’s

poetry, translated into English. In the main, other than regular diversions

into provocative showboating, such as My Dad was a solitary and barbarous

cunt, Houellebecq’s poetry is a series of terse, epigrammatic observations

on the human condition. It must be conceded that in most instances, endless

screeds of short, depressive homilies to decay, failure and loneliness do not

provide any great philosophical insights, though there are the occasional

passages of truly persuasive writing, such as -:

“We

may not live, but we get old all the same

And

nothing changes, nothing. Neither summer, nor things.”

Finally, there is the question of Houellebecq’s musical adventures.

His first effort, Le Sens du Combat (1996), was the recitation of some

early poems over a musical backing provided by the composer Jean-Jacques Birgé.

As the cheapest version I found online was £147, I decided I could live without

it. I am also living without Établissement d'un ciel d'alternance (2007), Houellebecq’s

most recent recording, again in collaboration with Birgé, as it is stuck in the

post with the Lovecraft book; don’t worry I will return to them in due course.

I am delighted to say that I have taken possession of Houellebecq’s 2000

recording, Presence Humaine and I’m very glad to have done so.

Houellebecq

doesn’t sing; instead he solemnly declaims his poetry in a voice that is

sometimes sombre, but oftentimes contemptuous, over a mid-70s style jazz rock backing

band who sound like Brand X on lithium for the first seven tracks. The last

three see him accompanied by a kind of cerebral synthpop backing that sounds

like an enthusiastic amateur with a yen for Blancmange or Yazoo. As someone

with a decent comprehension of written French, but only a rudimentary knowledge

of the spoken version, I am more at home with the sleeve than the libretto

(stop it!), in terms of comprehension. It is difficult to connect with the

package either in isolation or totality. However, there are two superior cuts

that hit the mark; when the band pick up the pace and start to drive, while

Houellebecq breaks off from his bad impersonation of Bryan Ferry on A Song

for Europe, to spit bile on the opening title track and the final ensemble

number, Plein été. These tracks justify the purchase, thankfully for a

tenner and not £147.

So,

while I await the delivery of a final book and CD, I mark the days off the

calendar until On Schopenhauer is published. Once that is out of the way, I may

allow myself to move on, though each subsequent Houellebecq novel will certainly

prick my attention, pausing only at this point to say he isn’t a French

literary messiah, but just another very naughty post-modernist boy.

No comments:

Post a Comment