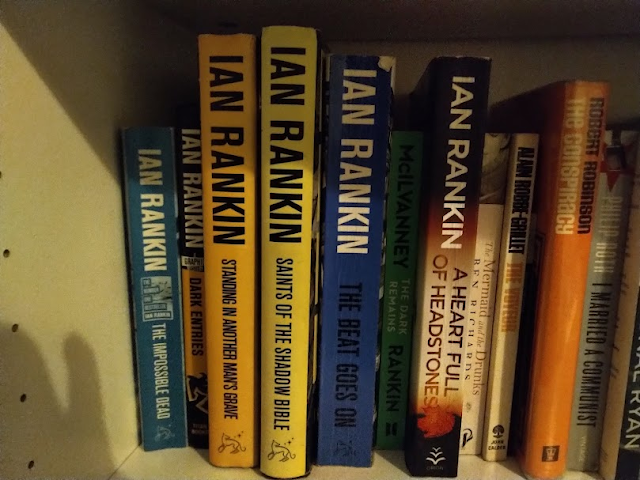

I love Ian Rankin's novels, especially the non-Rebus ones....

2024 is shaping up to be a pretty fine year, in terms of new books by my favourite writers. In chronological order of their projected release dates, I’m looking forward to Sixteen Again, Paul Hanley’s soon published tribute to The Buzzcocks and all they meant to him, before some real fiction heavyweights have their say. Irvine Welsh, Resolution (12th July), David Peace UKDK (1st August), Roddy Doyle The Woman Behind the Door (12th September), Michael Houellebecq Annihilation (19th September) and Ian Rankin Midnight & Blue (10th October).

In preparation for the final book on that list, I’ve set myself the task of reading the complete works of Fife’s finest purveyor of Caledonian Noir. This is no small undertaking, as Rankin has been publishing novels for nearly 40 years; not just the Inspector Rebus series, of which there are 25 volumes, plus a high volume of short stories, two stage plays and an autobiographical commentary on Rebus’s relationship with Scotland as a whole, but his non-Rebus oeuvre. Before embarking on this task, I knew that Rankin wrote novels utterly unconnected to Police Scotland’s most famous intuitive curmudgeon, because the first thing of his that I read was Doors Open, a rattlingly good art heist thriller, set in Edinburgh, though it was only this year that I realised I would have to make my way through the grand total of 11 novels, including one collaboration, a dozen short stories, a graphic novel and a stage play. Though I’ve still got a dozen Rebus novels to finish before I’m ready for the publication of Midnight & Blue, I’ve now finished the rest of Rankin’s work, which I’d like to discuss below.

The Flood (1986): Set in a fictionalised version of Rankin’s home village of Cardenden, a former coal mining settlement in the less salubrious part of Fife, his debut novel is perhaps the most consciously literary text of his entire published output. Starting in the early 1960s, it charts the miserable life of the outcast Mary Miller. As a child, she fell into a stream of pollution from the pit that flowed through the village, which turned her hair permanently white. Initially she was treated with sympathy by the local community, but all that changed when the young man who pushed her in, died in a workplace accident. In the present day, still shunned, Mary is a single mother caught up in a faltering affair with her son’s English teacher. Meanwhile, her son, Sandy, has fallen in love with a strange homeless girl, and, as both doomed relationships hit the rocks, mother and son are forced to come to terms with a terrible secret from Mary's past: Sandy is the product of his late grandfather’s rape of his mother. Nothing good can come of this situation, set amidst the unforgiving dark, suffocating, Calvinist village mentality. The book is both gripping and depressing. It is also considerably better than most of Rankin’s non-Rebus quasi juvenilia.

Watchman (1988): A preposterous espionage thriller, in the manner of Len Deighton, Watchman tells the story of Miles Flint, a surveillance officer who works for MI5. After two high-profile operations involving Flint go badly wrong, with deadly consequences, he is sent to Belfast to witness the arrest of some of the Boys. However, after accompanying a bunch of rather loathsome Loyalists (are there any other kind?), he discovers that what has actually been planned is the murder of the Ra men and then realises that his own life is at risk. As the executions are about to be carried out, Flint escapes with the aid of one of the Provos, who is supposedly a former UVF member who swapped sides after reading about the fellas on the blanket (aye right…). The two of them go on the run, while piecing together the bones of a conspiracy which goes right to the very core of the British Government. Fairly predictably, spilling the beans on this, allows them all to live happily ever after. Flint even manages to patch up his marriage, which had previously been badly on the skids.

Westwind (1990): The Zephyr computer system monitors the progress of the United Kingdom's only spy satellite. When this system briefly goes offline, Martin Hepton becomes suspicious following the death of a work colleague who suspected something strange is going on at the satellite facility where they both work, and then goes missing before winding up dead. Needless to say, Hepton doesn’t believe the official line of suicide. Refusing to stop asking questions, he leaves his old life behind, aware that someone is shadowing his every move. The only hope he has of getting to the bottom of this mystery is enlisting the services of his ex-girlfriend Jill Watson, a crusading journalist who believes his story. Rather a lot of cross and double-cross occurs on both sides of the Atlantic as Hepton, Watson and her new squeeze, the only astronaut to survive a suspicious space shuttle crash, outwit malfeasant security services and manage to live happily ever after. It’s daft, but very entertaining and hints at the three novels to follow.

Witch Hunt (1993): In the early 90s, recently relocated to rural France and finding that the Rebus books were niche fiction, rather than blockbuster airport reads, Rankin made the decision, presumably for financial rather than aesthetic reasons, to publish some mainstream thrillers under the nom de plume of Jack Harvey, combining his first-born son’s name and his wife’s maiden name. Stylistically, Witch Hunt, Bleeding Hearts and Blood Hunt are all cut from the same cloth; breathless action, one-dimensional or idee fixe characters, labyrinthine plot twists and unconvincing denouements but, as far as page-turners go, they aren’t a bad, undemanding read.

In Witch Hunt, the action begins with the sinking of a fishing boat in the English Channel in the middle of the night, and the evidence points to murder. Ex-MI5 operative Dominic Elder comes out of retirement to help investigate, as it appears that his long-time obsession, a female assassin known as Witch, may be responsible. Using the boat to get to England from France, Witch left a subtle trail of clues to announce her arrival and to warn off Elder, who knows her to be a resourceful enemy, always seeming to be a step ahead of the authorities. With an imminent summit of world leaders to be held in London, Witch's probable target seems obvious. A team of detectives and MI5 agents, and the terrorist, play cat-and-mouse with each other in Scotland, England, France, and even briefly visit a former associate of Witch in prison in Germany, before taking the enemy down, with only one high ranking casualty; the nefarious Home Secretary who turns out to be Witch’s long-estranged father.

Bleeding Hearts (1994): This is the only Rankin novel I know of that is written, only partly I’ll acknowledge, in the first person, though the rest of the narrative is told in the third person, which creates a slightly uncomfortable, if not clumsy, atmosphere. It is also the only novel I’m aware of that is told from the perspective of a haemophiliac hired assassin, one Michael Weston. Yes, we’re talking that level of reality as the wealthy father of a girl he killed by mistake years ago has sworn vengeance on the killer, hiring an American private detective, the deliciously crass Hoffer, to track Weston down. Hoffer does, but doesn’t pull the trigger, as the love of a good woman intervenes and Weston retires from the game, allowing him and Hoffer to part on equal terms with no blood spilled, of the clotted or unclotted variety.

Rankin has claimed that he wrote this book under the influence of Martin Amis's novel Money and that Weston was influenced by that novel's protagonist John Self, but I can’t see any connection myself.

Blood Hunt (1995): In this final Jack Harvey novel, Rankin recycles the character of Gordon Reeve, who was Rebus’s nemesis in the first novel in that series, Knots & Crosses, though he does imagine a different life for Rebus’s former SAS buddy.

The novel begins when Reeve takes a phone call informing him that his brother Jim has been found dead in San Diego. While in the USA to identify the body, Gordon realises that his brother was murdered, and that the police are more than reluctant to follow any leads. Retracing Jim's final hours, he connects Jim's death with his work as a journalist, investigating a multinational chemical corporation. Gordon soon discovers that he is being watched, so he decides to ask Jim's friends back in Europe for further information.

In London, he finds more hints, but no evidence for his brother's sources. After returning to his wife and son, he finds that his home has been bugged by professionals. Sending his wife and son to a relative, he determines to take on his enemy on his own. There are two parties after him: The multinational corporation, represented by Jay, a renegade SAS member, and an international investigation corporation, somehow connected with the case.

Travelling to France, in order to find out more from a journalist colleague of Jim's, they are attacked by a group of professional killers, resulting in multiple deaths, and leading to Gordon becoming a police target. Gordon decides to return to the USA, where he infiltrates the investigation corporation, and learns more about the history of the case. Then he travels to San Diego, to collect more evidence, and eventually returns to England, deliberately leaving a trail for Jay. Their long enmity leads Jay to follow Gordon to Scotland, where Gordon kills him and his team in a final showdown. Gordon manages to locate Jim's hidden journalistic material, thus enabling him to hopefully clear Jim's and his own name. It is by far the best of the three Jack Harvey novels and offers a glimpse into what kind of a writer Rankin would have become, if he’d decided to go down the espionage rather than the psychological police procedural route. Ironically, it was the success of his Rebus novels, not to mention their increasing complexity and the attendant length of time it took him to write the things, that caused Rankin to park the Jack Harvey project.

Beggars Banquet (2002): I read the entire collected Rebus short stories in The Beat Goes On, so when I got this one, I only read the non-Rebus ones and I like them tremendously. Well worth seeking out.

Doors Open (2008): As I mentioned earlier, this was the first Ian Rankin book I read and, only knowing his work from the Ken Stott Rebus dramas at that point, it certainly wasn’t what I expected. Mike Mackenzie is a software entrepreneur who has sold his company for a substantial amount of money but is now bored and looking for a new thrill. His new-found wealth has funded a genuine interest in art so when his friend Professor Robert Gissing presents him with a plan for the perfect crime, he is intrigued. With a vast collection but limited wall space, the National Gallery has many more valuable works of art in storage than it could ever display. The plan is to stage a heist at the Granton storage depot on "Doors Open Day" during which a selected group of paintings will be stolen. The gang will then give the appearance of having panicked and fled without the works of art but will have switched the real paintings with high quality forgeries good enough to convince anyone investigating the matter that no theft has been committed.

Intrigued, Mike willingly helps set that plan in motion. As they begin to plan it out, it becomes clear that they need some "professional assistance" and a chance encounter with Chib Calloway, a local gangster who Mike went to school with, fulfils that need, presumably as Big Ger was on holiday at that point. It’s a good old-fashioned heist yarn, with a surprisingly moral ending. I suppose if I hadn’t enjoyed it, I wouldn’t have embarked upon this journey through Rankin’s collected works.

A Cool Head (2009): It’s very fashionable to decry Tony Blair, simply on account of the fact he’s a war criminal who spent his entire Premiership toadying up to the Great Satan across the pond, but he did do some good things. The Quick Reads initiative was one of them. Quick Reads were launched by Blair on World Book Day 2006. By mid-2020, over 100 titles had been published, over 4.8 million copies had been sold and over 5 million copies had been loaned through libraries.

For those unfamiliar with the project, Quick Reads are a series of short books by bestselling authors and celebrities. At no more than 128 pages, they are designed to encourage adults who do not read often, or find reading difficult, to discover the joy of books. In a long-forgotten celebration of the philosophy of lifelong learning, Quick Reads were a collaboration between leading publishers, supermarkets, bookshops, libraries, government departments, the National Institute of Adult Continuing Education (NIACE), Arts Council England, the BBC, World Book Day, National Book Tokens and more. They are used as a resource for adult literacy teaching and have been used in Skills for Life and ESOL classes in colleges, community centres, libraries, prisons and workplaces across the country. They have also been used in hospitals, stroke recovery units, dyslexia centres, care homes, family learning groups, pre-schools, organisations working with homeless people and traveller communities, and Army and RAF bases. In a survey covering 50,000 readers in 2010, 98% said that Quick Reads had made a positive impact on their lives. Certainly, as someone who taught for many years in Adult Education, I can vouch for their value in demystifying the vexed concept of reading fiction for pleasure. In 2018, the programme was due to come to an end because of a lack of funding. Another thing to thank the Tories for, eh?

What has this to do with Ian Rankin? Well, in 2009, Quick Reads published his contribution to the series, A Cool Head. It tells the story of Gravy, who works in a graveyard. One day his friend turns up in a car he doesn't recognise. His friend has a bullet in his chest. Gravy is asked to hide the gun and the body. In the back of the car is blood, and a bag full of money. Soon Gravy is caught up in a robbery gone wrong and is pursued by some desperate and mysterious men as well as the police. Thanks to Ian Rankin for writing this story.

Dark Entries (2009): I’ll come clean with you; this is the Ian Rankin book I liked the least. In fact, I probably dislike it, because of my own prejudices. You see, it’s a graphic novel or, if you’re an adult, a comic. The story involves DC Comics character John Constantine, the series Hellblazer, apparently.

The plot involves John Constantine being convinced to enter a reality television programme which has suffered several strange hauntings, which is clearly a thinly veiled satire of Most Haunted and Big Brother. The set turns out to be not a television programme made for humanity, but for the denizens of Hell, and John must work out a way to escape from this. I’m not really sure if he did and, frankly, I’m not bothered. Then again, I doubt I’m the target demographic for such balderdash.

The Complaints (2009): The character of Malcolm Fox, who ends up in at least 4 of the later Rebus novels, as well as the two dedicated solely to him, is the best and most satisfying Rankin creation outside of Rebus and Siobhan Clarke, in my opinion. A dogged, recovering alcoholic loner, with a bad marriage behind him, a drunken underachieving sister with an attitude problem and an ailing father in a care home, Fox throws himself into his job with silent gusto. The fact is his job entails investigating potential misconduct by other officers, hence The Complaints, makes him a figure to be truly despised by those on the force as well as off it. The fact he somehow manages to shrug this shroud of enmity off and solve complex, intractable cases shows us why he ends up back in CID.

In The Complaints, Fox and his team are tasked with investigating Detective Sergeant Jamie Breck, suspected of being a member of a child pornography ring. However, Breck is in turn investigating the death of Vince Faulkner, who was in an abusive relationship with Fox's sister. This brings Fox into direct contact with Breck, and as he develops both a friendship and a working relationship with him, he begins to doubt the validity of his assignment. Despite his personal connection to the case, and against protocol, Fox gets involved in the investigation into Faulkner's death. This brings him into conflict with Breck's superior officer, who harbours a dislike of Fox for investigating a corrupt officer under his command.

Eventually, Fox and Breck are both suspended and Fox is also placed under investigation. However, they continue to investigate Faulkner's death, discovering that he had links to a bankrupt property developer who appears to have committed suicide. This leads to further links to members of the criminal underworld, and in turn to a senior member of the police force, who is found to be responsible for having Breck framed and for having Fox placed under investigation. When Fox comes out on top, I actually punched the air in celebration, such is the superb characterisation Rankin has employed to turn a potentially mealy-mouthed, paper clip counter into a sleuth supreme. Also, Fox’s activities take place back in familiar Edinburgh locations which, as Rankin became ever more certain of his craft, are the best and most fitting place for his fiction.

The Impossible Dead (2011): The second and, sadly, seemingly final Malcolm Fox novel is even more enjoyable than The Complaints, partly because we get to travel to Rankin’s home turf of the Kingdom of Fife. Proper Fife as well; Kirkcaldy, not the Vichy Fife of Dunfermline or the lah di dah East Neuk and that unspeakable posh place east of Leuchars.

Fox and his team, Tony Kaye and Joe Naysmith, are assigned to an investigation into Detective Sergeant Paul Carter, who has been found guilty of misconduct. Fox’s job is to reassure the Fife Constabulary top brass that the other Kirkcaldy police are clean. Fox visits Paul’s uncle Alan, a seemingly jovial retired Polisman who had reported Paul in the first place and is drawn into the murder investigation when Alan is killed, and Paul is framed for it. Fox and his team must dodge, while exploiting as sources, not only the hostile Kirkcaldy police but contingents of Fife headquarters CID, Murder Squad, and even an emissary from London’s Special Branch.

When Fox visited him, Alan Carter was investigating the suspicious 1985 death of an Edinburgh lawyer named Francis Vernal, who was involved with Scottish Nationalist paramilitaries in the 1980s. Fox becomes obsessed by Vernal’s story, in part because there are similarities between Vernal’s death and Carter’s murder. He interviews various former associates of Vernal, including his onetime law partner, his widow, a madman, a TV personality, and a Chief Constable who is herself trying to deal with a group of terrorists. Eventually Fox identifies the person who killed both Vernal and Carter, but Fox has to risk his own life to capture them. He does, coming out clean as a whistle, having wrecked the career of the Chief Constable of Fife in the process. So it goes, eh?

Dark Road (2013): Thus far in his career, Ian Rankin has written three plays: the Rebus connected A Game Called Malice and Long Shadows, which I’ll talk about next time, as well as the unsettling Dark Road. Bearing in mind I’ve not seen any of his plays performed, I can only talk about them in terms of how they appear on the page. Co-written with Lyceum Edinburgh’s director Mark Thomson, the play is set in modern-day Edinburgh and follows Scotland's first (fictional) female Chief Constable Isobel McArthur now Chief Superintendent of Edinburgh following the creation of Police Scotland, as she considers retirement and ponders writing a book. As part of that she reviews the case of Alfred Chalmers a serial killer who killed four girls a quarter of a century previous, a conviction she has long held doubts about. What follows is a thriller that throws herself, her daughter and her colleagues into a psychological battle against Chalmers. As a piece of writing, the ending may be a tad predictable, but I’d imagine it is a bit of a chiller to sit through. I’d like to see this live I must admit.

The Dark Remains (2021): While I’ve long been an admirer of the football writing of the esteemed Hugh McIlvanney, I’m sorry to report I was unaware of the works of his brother William. This is a situation I intend to remedy when time allows. Following William McIlvanney’s death in 2015, he left among his papers an unfinished draft of a police procedural, involving his Glasgow copper Jack Laidlaw. It was the fourth Laidlaw novel but set chronologically before the other three. Ian Rankin took on the project and produced the vivid and compelling The Dark Remains.

Jack Laidlaw has been moved to the Central Division of the Glasgow Crime Squad. He is a DC working for DI Ernie Milligan. Robert Frederick the commander of the Glasgow Crime Squad assigns DS Bob Lilley to keep an eye on him, saying Laidlaw's reputation has always preceded him .... who has he rubbed up the wrong way this month? .... he’s good at the job, seems to have a sixth sense for what’s happening on the streets (but) he needs careful handling, if we’re to get the best out of him.

The novel is set in October 1972, early in Laidlaw's career. Bobby Carter the right-hand man and lawyer cum money launderer for Cam Colvin one of Glasgow's top gangsters has disappeared, and then his body is found, in enemy territory. John Rhodes is Colvin's main rival; not minor gangsters like Matt Mason and Malky Chisholm. Milligan pontificates to his team that the graffiti tells him that the Cumbrie are encroaching on the Carlton turf. A stabbing is one hell of a calling card, wouldn’t you agree? He assumes, like other gangsters, that a rival gangster arranged Carter's death, and gang warfare intensifies. But Laidlaw sees in Carter's home evidence of recent painting to cover up bloodstains from a domestic dispute after Carter was stabbed by his bullied wife and children. His wife eventually confesses to Laidlaw, to keep the children out of it. Laidlaw bypasses Milligan, who he despises, by reporting directly to Commander Frederick. When the team are celebrating the end of the case, Frederick says privately to Lilley that if he doesn’t manage to detonate himself in the near future, he might be in line for a swift promotion .... (although he is) not exactly a team player. This is a great book by two great writers about a great fictional cop.

In a dozen books time, I look forward to discussing 25 great books involving Scotland’s greatest fictional cop.

This is a tremendous article

ReplyDeleteThank you

If you ever want to meet Ian Rankin

Go to the Oxford bar every afternoon in the literary festival as he pops in

If you enjoy reading fact based espionage thrillers, of which there are only a handful of decent ones, do try reading Bill Fairclough’s Beyond Enkription. It is an enthralling unadulterated fact based autobiographical spy thriller and a super read as long as you don’t expect John le Carré’s delicate diction, sophisticated syntax and placid plots.

ReplyDeleteWhat is interesting is that this book is so different to any other espionage thrillers fact or fiction that I have ever read. It is extraordinarily memorable and unsurprisingly apparently mandatory reading in some countries’ intelligence agencies’ induction programs. Why?

Maybe because the book has been heralded by those who should know as “being up there with My Silent War by Kim Philby and No Other Choice by George Blake”; maybe because Bill Fairclough (the author) deviously dissects unusual topics, for example, by using real situations relating to how much agents are kept in the dark by their spy-masters and (surprisingly) vice versa; and/or maybe because he has survived literally dozens of death defying experiences including 20 plus attempted murders.

The action in Beyond Enkription is set in 1974 about a real maverick British accountant who worked in Coopers & Lybrand (now PwC) in London, Nassau, Miami and Port au Prince. Initially in 1974 he unwittingly worked for MI5 and MI6 based in London infiltrating an organised crime gang. Later he worked knowingly for the CIA in the Americas. In subsequent books yet to be published (when employed by Citicorp, Barclays, Reuters and others) he continued to work for several intelligence agencies. Fairclough has been justifiably likened to a posh version of Harry Palmer aka Michael Caine in the films based on Len Deighton’s spy novels.

Beyond Enkription is a must read for espionage cognoscenti. Whatever you do, you must read some of the latest news articles (since August 2021) in TheBurlingtonFiles website before taking the plunge and getting stuck into Beyond Enkription. You’ll soon be immersed in a whole new world which you won’t want to exit. Intriguingly, the articles were released seven or more years after the book was published. TheBurlingtonFiles website itself is well worth a visit and don’t miss the articles about FaireSansDire. The website is a bit like a virtual espionage museum and refreshingly advert free.

Returning to the intense and electrifying thriller Beyond Enkription, it has had mainly five star reviews so don’t be put off by Chapter 1 if you are squeamish. You can always skip through the squeamish bits and just get the gist of what is going on in the first chapter. Mind you, infiltrating international state sponsored people and body part smuggling mobs isn’t a job for the squeamish! Thereafter don’t skip any of the text or you’ll lose the plots. The book is ever increasingly cerebral albeit pacy and action packed. Indeed, the twists and turns in the interwoven plots kept me guessing beyond the epilogue even on my second reading.

The characters were wholesome, well-developed and beguiling to the extent that you’ll probably end up loving those you hated ab initio, particularly Sara Burlington. The attention to detail added extra layers of authenticity to the narrative and above all else you can’t escape the realism. Unlike reading most spy thrillers, you will soon realise it actually happened but don’t trust a soul.